Not all progesterone’s are created equal

April 20th, 2021A review of progesterone and breast cancer risk by Dr. Nyjon K Eccles, BSc MBBS MRCP PhD

Dr. Nyjon Eccles is known as ‘the natural doctor’ and practices from Harley Street in London, England and is one of the UK’s leading Integrated Medicine doctors with a special interest in breast cancer.

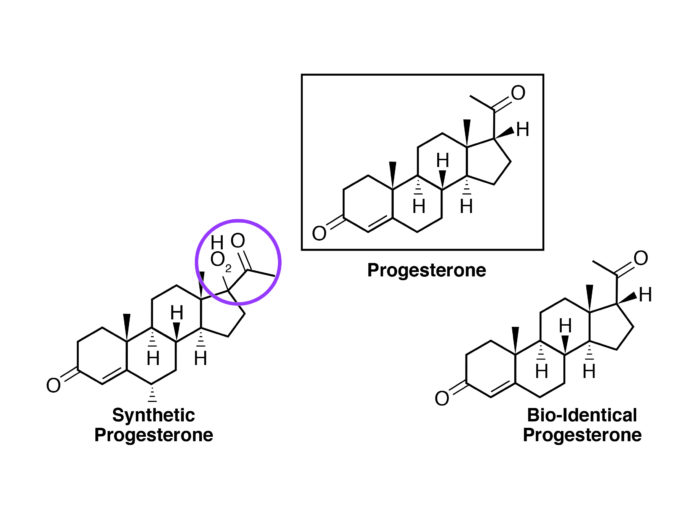

His article is a summary of some of the evidence surrounding the use of natural progesterone vs. synthetic forms and it seeks to clarify the debate as to whether all types of progesterone have the same physiological and clinical effects, or whether there is indeed evidence to suggest that the synthetic progesterone’s (progestins) differ in effect to progesterone in its native molecular form.

Note: From herein progestins will refer to the synthetic form and progesterone to the natural form.

I am indebted to the commentary and detailed review published by Dr. Kent Holtorf in 2009. Much of his article is so pertinent to this discussion that I have pasted in some sections of it. Some of this is detailed science for those who have the appetite for it, but I have also highlighted the key conclusion points for patients in the summary at the end.

A lot of confusion abounds on this topic, and in my experience most doctors are confused about this. As with all truth seeking, this can only come from a critical look at the published data and not from mainstream media or expressed opinions that do not reference the published science.The risk of breast cancer is increased more with the addition of synthetic progestins to estrogen in HRT for those with menopausal symptoms than just estrogen alone (1).

In breast cancer survivors, progestin use is associated with an increased breast cancer risk compared with its non-use (2). However, outside pregnancy, natural progesterone whether endogenously produced or exogenously administered does not have a cancer-promoting effect on breast tissue. Progesterone is added for postmenopausal women to prevent against the carcinogenic effects of estrogen on the uterus (3). In premenopausal women, oral contraceptive pills that contain progestin appear to provide a protective effect against endometrial cancer.

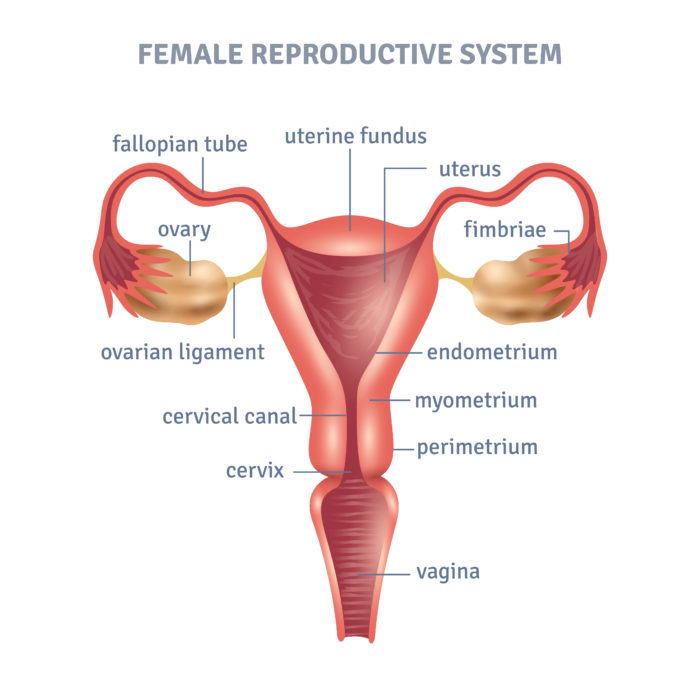

Progestogens work to counteract the effect that estrogen can have on the endometrium (see figure 1). The effect of progestogens are great the more days each month they are added to estrogen and how obese the person in question is (3).

Figure 1: The position of the endometrium in a woman’s uterus.

A secondary follow up of a French study (4) that looked at the incidence of breast cancer in approx. 80,000 women who had been taking HRT with estrogen and various progestogens led to the notion that progesterone may increase breast cancer risk. These results went against the popular thinking that this hormone is protective against breast cancer.

Fournier studies

The original Fournier et al’s (5) study of 80,391 postmenopausal women looked at how the relationship between different progestogens (that is, any molecule with a structure like the natural progesterone hormone) in combination with estrogens raised the risk of developing breast cancer. This showed that lowest progesterone had the lowest risk, and this was lower than the risk of no treatment at all (2).

Figure 2: The difference between a synthetic progesterone (progestin) and a natural (or bioidentical) progesterone.

The second study (5) (which was with the same patient population as the first) came back with the results that the risk with estrogen plus progesterone was less than the risk of estrogen alone and again, natural progesterone has the lowest risk of all.

It must be noted that:

- These studies were based on the use of oral progesterone

- They did not look at the effect of natural progesterone on it’s own, only estrogen plus progesterone

- The more accurate commentary on the data would be that the use of natural progesterone decreased the risk of breast cancer when caused by long term estrogen use (i.e., risk 2.1 to 1.7).

- Women who were seen to have a low progesterone/estradiol ratio were more likely to develop atypical beneign breast disease. This has an increased risk of turning into breast cancer (6).

An increased risk of breast cancer (7) has also been associated with low endogenous luteal progesterone levels in premenopausal women

One small study (8) looked at the risk of breast cancer with topical progesterone (10-30 mg progesterone daily). This showed the breast cancer risk to be reduced by half in those using topical progesterone for 3 years or more.

Estrogen and progesterone receptor positive cancers

There is a general view that having a breast cancer that is both estrogen receptor positive (ER+) and progesterone receptor positive (PR+) may be worse than having ER+ alone. Around 70% of breast cancers are ER+ and 87% of these are also PR+. Therefore, hormone receptor status is extremely important when treating breast cancer.

That being said, it is seen that women who present with high PR+ and ER+ levels often have the best chance of surviving. This information is often not passed on to patients unfortunately. Whereas estrogen can promote a tumor’s growth, progesterone slows growth. As estrogen and progesterone receptors are directly involved in switching some 470 genes on and off, they affect cell behaviour, and are found in many of our cells across the body, including breast cells. While estrogen activates its receptor, turning on genes that stimulate cells to keep dividing, driving tumor growth, sufficient progesterone on the other hand will slow down the estrogen-fuelled growth and division of these cells.

Author Dr. John Lee, M.D*, detailed this years ago. His approach was that the progesterone receptors are activated by progesterone and therefore attach themselves to the estrogen receptors, which in turn stops estrogen from turning on genes that promote the growth of cancer cells. In comparison, progesterone activates the genes that promote cancer cell death (apoptosis) and encourage healthy, normal cells to grow.

*Author of “What Your Doctor May Not Tell You About Breast Cancer”

A failure to grasp this important concept has led to many doctors ‘villainizing’ progesterone. A study which was published in the scientific journal Nature, led by Dr. Jason Carroll for Cancer Research UK, brought more awareness to the benefits of progesterone and progesterone receptor status. This study showed that there is a clear link between how good a woman’s survival rate is in relation to whether the cancer has both ER and PR status. This belief is that these cancers are more “treatable” than hormone-receptor negative cancers.

Carroll’s study found that progesterone – via the progesterone receptor – moderates how the estrogen receptor works. They found that the progesterone receptor, in effect, ‘re-programs’ the estrogen receptor, changing the genes that it influences. (For further details see Nature, volume 523, pages 313–317, 16 July 2015). This study highlights an important function for the PR receptor in modulating the behaviour of the ER in breast cancer. It confirms the previously published work that has suggested the same effect.

It is most important to note that the overall effect of progesterone on cancer cells was to cause the cells to stop growing as quickly. Carroll’s findings clarify why women who have both ER+ and PR+ potentially have a better outlook than those with just ER+ or receptor-negative cancers; assuming, that is, that progesterone forms part of their treatment regime. Progesterone and HER2 in Breast Cancer HER2 and progesterone seem to be important in controlling metastatic dissemination of tumor cells prior to the detection of a primary tumor.

It has been long known in the field that synthetic progestins do not stimulate the activation of gene P53, a tumor suppressor and repair gene, like natural progesterone receptors do (4). Gene P53 works to protect the cells from cancerous changes as progesterone attaches itself to progesterone receptors.

Maintaining healthy natural progesterone levels, avoiding synthetic progesterones and the downregulation of HER2 seems to be a desirable treatment objective, and whilst Herceptin® is the drug of choice for HER2, one author has noted that daily consumption of 25 grams of flaxseed has been shown to decrease HER2 expression by 71%, which appears to outperform the drug, without the side effects of the drug.

Summary

- The use of synthetic progestins in breast cancer survivors is associated with increased risk of recurrence, whereas natural progesterone use does not increase risk.

- The addition of progesterone to estrogen negates the increased risk of breast cancer seen with estrogen alone.

- Women who have an excess of estrogen relative to progesterone (low progesterone/estradiol ratio), are more likely to have atypical benign breast disease and increased risk of developing breast cancer.

- Women with breast cancers with high levels of estrogen receptors and progesterone receptors have the best chance of survival.

- Sufficient progesterone will slow down the estrogen-fuelled growth and division of breast cancer cells.

- Natural progesterone, (but not synthetic progestins), activate genes that promote death of cancer cells (apoptosis) and the growth of healthy, normal cells.

- Carroll’s study published in Nature in 2015 showed that progesterone acts as a suppressor of estrogen stimulated breast cancer cells.

- P53 is a repair gene, which protects cells from cancerous change if natural progesterone can attach itself to progesterone receptors. This effect is not seen with progestins.

Yet, despite all these positive facts, the addition of natural progesterone to estrogen receptor modulation is not currently standard oncological practice.

References

- Jerry DJ. Roles for estrogen and progesterone in breast cancer prevention. Breast Cancer Res. 2007, 9: 102-10.1186/bcr1659.

- Beral V, Million Women Study Collaborators. Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet. 2003, 362: 419-427. 10.1016/S0140- 6736(03)14596-5.

- Beral V, Bull D, Reeves G, Million Women Study Collaborators. Endometrial cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in the Million Women Study. Lancet. 2005, 365: 1543-1551. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66455-0.

- Fournier et al J Clin Oncol 26 (8):1260-1268, 2008. [Needs author’s initial, and article title]

- Breast Cancer Res Treat 107: 103-111, 2008. [Author, title?]

- Sitruk-Ware et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 44, 771, 1977. [Needs article title]

- Micheli et al. Int J Cancer 112, 312-318, 2004. [Needs author’s initial, and article title]

- Plu-Bureau G, et al. Cancer Detect Preve 23(4), 290-296, 1999. [Needs article title]